How do we solve Britain’s energy bill crisis?

It could be a winter of discontent. Millions of people are braced for eye-watering energy bills. Some may choose not to heat their homes and others could refuse to pay, perhaps amid mass civil disobedience. And the government is rudderless — waiting for the Tory Party to crown a leader next month who will have just a matter of weeks to decide on a way forward.

Into the vacuum last week stepped Gordon Brown. In demands designed to shame ministers for their inaction — and possibly also the leader of the opposition — the former Labour prime minister called for the energy price cap to be scrapped; payments to vulnerable households from October; a “watertight windfall tax” on energy companies; and even nationalisation for those suppliers that cannot bring bills down.

Brown’s intervention drew on his experience of the 2008 financial crash. Indeed, he painted a direct parallel with the government’s bailout of the banks and repeated a call for an old favourite: a tax on City bonuses to fund the huge cost of helping stricken households.

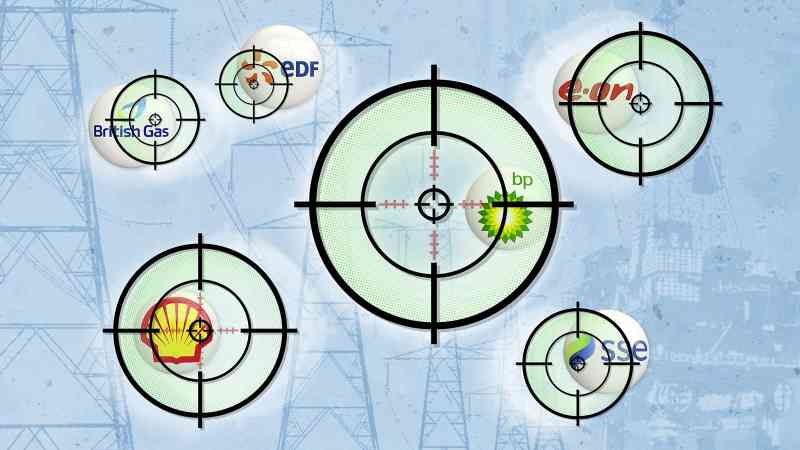

Who should pay?While Brown’s demands were intended to jolt ministers out of their summer slumber, they also reignited the question of who is to blame for the mess we’re in — and, by extension, who should foot the bill. With companies such as BP and Shell making vast profits from inflated oil and gas prices, the energy sector has seemingly overtaken the banks as public enemy No 1.

It is a point not lost on executives. BP boss Bernard Looney told analysts earlier this month that the cost of living crisis is a “very, very difficult place for people”.

“We get it,” he added. “So the question is: what can we do to help?” According to Looney, BP is helping by investing in green energy in the UK, creating jobs here, and paying taxes. That tax burden will be even higher after the government introduced a windfall levy earlier this year on North Sea oil and gas producers that lifted their corporation tax rate to 65 per cent. That measure is expected to raise £5 billion, and came into force only after much prodding by Labour.

Could the oil majors go further, and make a voluntary offering to help households? A hardship fund might be one option, though it is not clear how such a pot of money could be distributed to those most in need, or whether it would fall foul of competition law. Among the energy retailers — the likes of Eon and British Gas — there are individual schemes to help squeezed consumers. Energy UK, a trade body, said retailers already stump up £33 million in hardship funds on top of the £1 billion they are required to put into schemes such as the Warm Home Discount.

The retailers are at pains to insist that they are not banking huge profits from soaring gas prices, but are simply passing on the cost to consumers. An industry source said: “Most suppliers aren’t making any money and haven’t been for ages.”

Last month, Centrica reported a surge in half-year operating profits to £1.3 billion and reinstated its dividend. Yet most of that boost came from high prices supporting its North Sea oil and gas and nuclear businesses; profits at its British Gas arm fell 43 per cent.

Chris O’Shea, Centrica’s boss, said: “Energy retail in the UK is a risky business.” This was a nod to the rash of energy suppliers that have gone bust in recent years because they were thinly capitalised and could not survive the sudden increase in gas prices as countries emerged from Covid.

Banking crisis playbookBrown seemed to conflate the vastly profitable oil and gas producers with the rather shakier energy retailers — perhaps deliberately, to kick-start a conversation. His wider intent may have been to reframe the debate, according to Michael Jacobs, professor of political economy at Sheffield University, who advised Brown on energy in his time in No 10. “What’s interesting about Gordon’s intervention is that he’s saying we should not be having high bills in the first place — rather than having high bills and then trying to give people money to pay them,” he said.

This approach is more in keeping with that of France, where bill rises have been capped at 4 per cent — albeit by having the taxpayer pick up the cost through a full takeover of state energy giant EDF.

Brown’s proposed nationalisations echo the stakes the government took in British banks at the height of the financial crisis — but come with an array of problems. “I think finding a way to properly target handouts to the most vulnerable households would be far better than nationalising energy firms,” said Karl Williams, a senior researcher at free market think tank the Centre for Policy Studies. “For one thing … look at how long it took to divest the stakes we held in some of the banks after the crisis.”

After Covid, he said, “there is very much an attitude that in situations like this, the government should step in. But if energy prices stay elevated, can we sustain that expenditure for several years?”

Jacobs said: “The interesting question will be, is it cheaper to take over firms, or simply allow them to raise energy bills and then subsidise consumers?” Bulb, the failed supplier that is already in government hands, has cost taxpayers nearly £2 billion so far and is buying energy on the spot market at vast cost.

Whoever owns the energy companies, many people believe some sort of immediate help is required by October, when the price cap will rise again — with some industry sources claiming to be genuinely alarmed by the possibility of social unrest. This help could be distributed in blanket form — as with the £400 payment the government has already promised to all households this winter — or via the benefits system to reach the most vulnerable. Labour, meanwhile, has called for the axing of prepayment meters, which are typically used by poorer households and are easier to disconnect for non-payment. Tomorrow, it is set to call for an expansion of the windfall tax to raise at least an extra £2 billion to fund more help for households and businesses.

Searching for solutionsBeyond October, a recipe is needed for a new, improved energy market.

Some campaigners have called for the standing charge on bills to be scrapped because it penalises people who are trying to cut their energy use. Last month, the energy regulator Ofgem launched a review of the charge, which helps pay for the costs of collapsed energy suppliers. But it warned that those costs might have to be dumped on the unit cost of energy — the other part of a bill.

Energy suppliers have backed the introduction of a social tariff, which would cap costs for the poorest households and be funded by better-off consumers. ScottishPower and Eon have now tabled the creation of a special fund that would allow energy bills to be frozen and spread out the cost of higher prices over time.

Longer term, officials are looking at severing the link between the costs of gas and electricity. Typically, unit costs are set at the price of the most expensive unit in the system; at present, that is clearly gas — and by some margin — but cheaper electricity from renewables such as windfarms is being priced the same. Some electricity generators on older contracts are banking good money from this.

However Danny Newport, a former civil servant at the business department who is now head of net zero at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, said such a move would be “fraught with legal difficulties” as it would mean ripping up long-standing contracts.

An alternative might be to extend the windfall tax to include electricity generators such as nuclear power plants and windfarms. This idea was floated by former chancellor Rishi Sunak earlier this year before being dropped on the basis it might discourage investment. Newport said: “Extending the tax is probably a more legally defensible way of getting at those windfall profits and getting them back into consumers’ pockets.”

Other schemes could include the use of “block pricing”, whereby households are sold a chunk of energy at a fixed lower price but anything above that allowance is charged at higher rates. “It doesn’t make the power system as a whole cheaper, but it is a nice way of making sure that everybody has a kind of a basic amount,” said Dustin Benton, policy director at the Green Alliance think tank.

One former Ofgem insider said any change to the market would need to “maintain the competitive elements and dynamism”. They added: “You still want people to be responding to the price signals in the market, because high prices are reflecting scarcity to some degree.” Those signals, in turn, prompt customers to rein in energy use.

More work could be done to encourage consumers to use less energy; public information campaigns are under way in Germany, for example. But this approach can be perilous: in the UK, Ovo Energy was attacked earlier this year for recommending customers do star jumps to keep warm. Longer term, better home insulation in Britain’s old housing might stave off future crises. “There’s a lot you could do in terms of a big energy-efficiency rollout, but it could take the best part of a decade to do the whole building stock,” said Benton.

Such measures would be married with efforts to boost energy supply. The government has already put ageing coal-fired power plants on standby for this winter, and has hired consultants to help it better understand the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market, on which the UK is relying to bridge any shortfall in gas supplies from Europe. It is also working with Centrica to reopen the Rough gas-storage facility. And last week, the National Grid opened talks with businesses about a new scheme that would pay firms and homes to wind down their energy use this winter at peak times in the evening.

Brown’s intervention may be successful in that it underlines the scale of the challenge ahead. “These energy bills will be unpayable. When the Tory Party candidates come out of the leadership race, they will realise that we are in emergency conditions again,” said Jacobs. “And in an emergency, you’re not constrained by the same rules as in normal times.”

How are firms in other sectors helping?Amid dire warnings about energy prices this winter, the question being asked is: what can businesses do to ease the pain?

Banks and other lenders have been warned by the Financial Conduct Authority to make sure struggling customers are not unfairly treated if they fall behind on loan repayments. Meanwhile, Morrisons is offering a free kid’s meal for every adult one bought in its 402 cafés, and it is donating food to holiday clubs. And children can eat for £1 in Asda’s cafés regardless of how much their parent spends, while Clubcard holders can get a free meal for their children when they buy a piece of fresh fruit in Tesco’s cafés.

However, the supermarkets were criticised by the RAC last week for failing to pass on lower wholesale fuel costs to customers.